Talking Early Years: In conversation with Eunice Lumsden

Change the Way you Greet them There is a lot of concern about recently qualified staff who appear…

November 28th 2025

I’ve just finished recording a podcast with Professor Sam Wass, and I’m still buzzing. He is Director of the Institute for the Science of Early Years at the University of East London. You may also know him from The Secret Life of Four-Year-Olds. His research is fascinating because it brings neuroscience right into the nursery, helping us understand what children’s brains are telling us about their experiences.

Sam has that rare ability to take complex neuroscience and make it feel utterly practical for those of us working in nurseries every day. What struck me most is his reminder that young children experience the world in a completely different way from adults. Their brains are wide open, flooded with every sound, colour and movement. Meanwhile, we adults who can filter distraction tend to seek out calmer environments. Yet babies, whose brains struggle to filter anything, are often placed in the noisiest, busiest rooms. We’ve got it the wrong way round.

Sam’s research brings neuroscience directly into early years settings. He uses microphones, cameras and stress monitors to measure how babies and young children actually experience the environments we create for them. This is not guesswork. It’s science showing us what their brains are trying to tell us.

And what they’re saying is clear: space matters. Not square metres on a floor plan, but the actual sensory quality of the space. Babies need small, calm areas where they can retreat, tune out the noise and tune into learning. Their brains find it hard to filter out noise, movement, and distraction. Imagine being in a room with 20 people talking at once, bright colours, constant movement, and no quiet corners, that’s daily life for many under-fives. They respond by finding little corners or nooks because they’re trying to simplify the world around them so their brains can cope. When we overcrowd rooms or fill every inch with visual and auditory clutter, we make learning much harder for them.

Relationships matter too. Babies thrive on simple, repetitive, predictable interactions. All those moments adults sometimes dismiss, banging a spoon, dropping a toy again and again, pressing a button repeatedly are not trivial irritations. They are sophisticated experiments in prediction. If I do this, what happens next? If I do it again, will you respond the same way? That’s how the motor and sensory parts of the brain learn to communicate. It’s early science, happening right in front of us.

This is why skilled baby educators are essential. They aren’t babysitters. They’re interpreters of learning, helping parents understand what their babies are really doing and why it matters. They also need the confidence to work responsively, knowing when a child needs predictability and when they’re ready for something new. It’s a subtle dance, and it takes knowledge, patience and presence.

What I took most from our conversation is this simple truth: babies are not mini older children. Their brains are wired differently, and our practice must reflect that difference. If we don’t, we risk designing environments and routines that work against how young children learn best.

Change the Way you Greet them There is a lot of concern about recently qualified staff who appear…

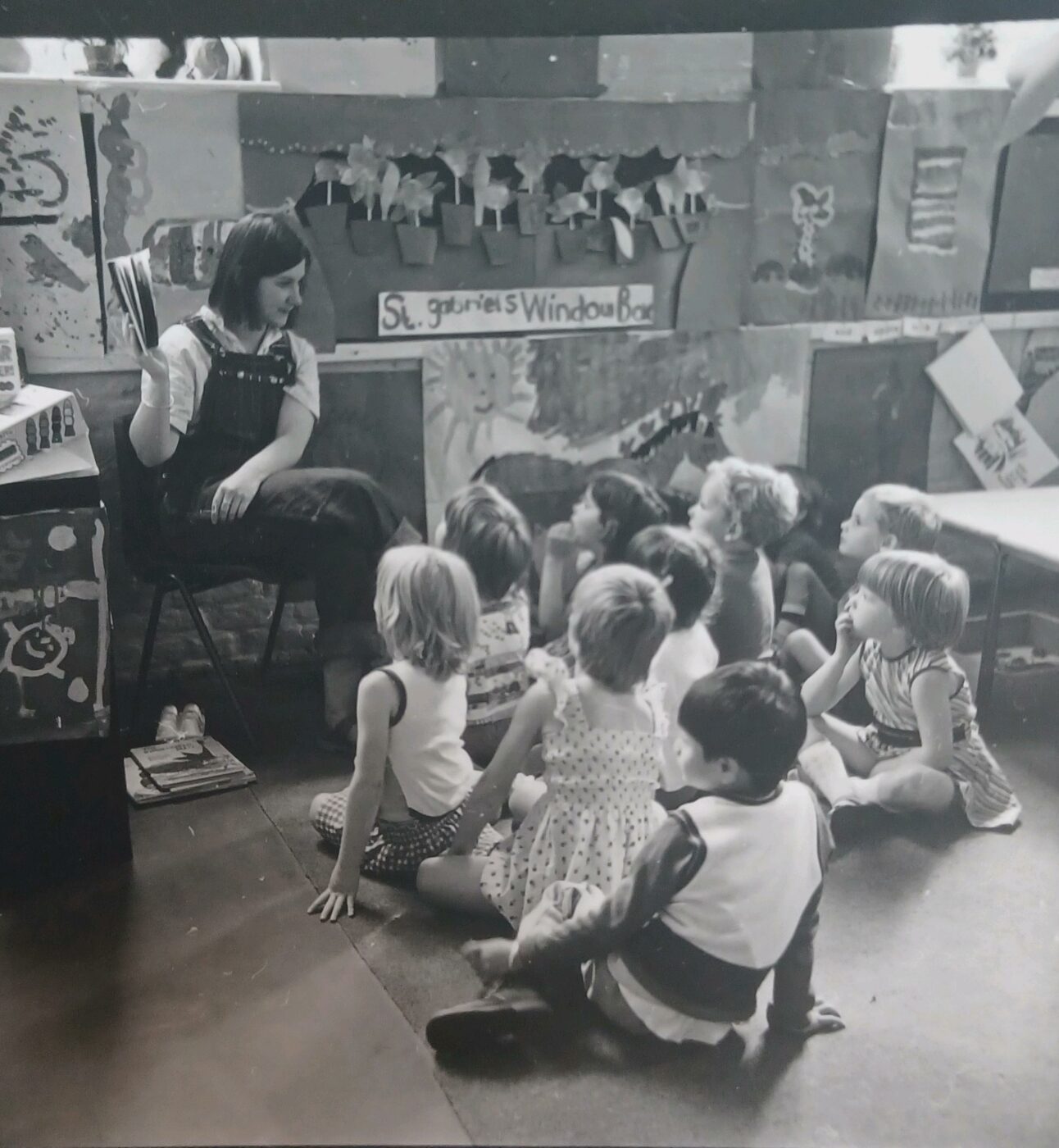

The Year That is 2023 – This year, we are proud to celebrate 120 years of LEYF. It’s been fascinating to reflect back on what has changed over…

I was very pleased to talk to Julian Grenier, Headteacher of Sheringham Nursery School in Newham in this month’s episode of Talking Early Years. He and I have…